I’m thrilled to host author Michael Niemann as my guest blogger this week. Michael’s latest novel, Illegal Holdings, launched March 1, the third in his Vermeulen Thriller Series. Michael uses his real world travels and experience to imbue his fiction with truth. Click here to read more about Illegal Holdings on Alison McMahan’s blog.

Michael Niemann grew up in a small town in Germany,

Michael Niemann grew up in a small town in Germany,  ten kilometers from the Dutch border. Crossing that border often at a young age sparked in him a curiosity about the larger world. He studied political science at the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms Universität in Bonn and international studies at the University of Denver.

ten kilometers from the Dutch border. Crossing that border often at a young age sparked in him a curiosity about the larger world. He studied political science at the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms Universität in Bonn and international studies at the University of Denver.

During his academic career he focused his work on southern Africa and frequently spent time in the region. After taking a fiction writing course from his friend, the late Fred Pfeil, he switched to mysteries as a different way to write about the world.

Public Transit African Style

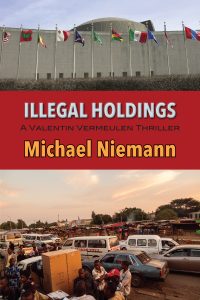

The cover of Illegal Holdings shows a busy urban scene from Maputo. A couple of cars, a pickup and a bunch of vans. Those vans are called chapas in Mozambique. The name derives from the Portuguese word for license plate. Chapas are the primary means of urban transport in Mozambique. Today’s vans are mostly Japanese and Korean makes. The drivers ply regular routes, pick up passengers when flagged down and let them off when asked. The fare beats the official buses (where they exist) and certainly the metered cabs tourists take.

My first experience with this means of transport was in Botswana in 1989. I was a poor student doing research and found that the hotel accommodation in Gaborone was scarce and expensive. After asking around, I found that there were cheaper rooms in a suburb called Mogoditshane.

poor student doing research and found that the hotel accommodation in Gaborone was scarce and expensive. After asking around, I found that there were cheaper rooms in a suburb called Mogoditshane.

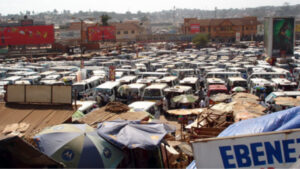

“How do I get there?” I said, thinking there’d be a bus line. Well, there wasn’t. Instead a friendly soul pointed me to the Broadhurst Combi Terminal near the railway station.

What I found was a huge parking lot filled with combis, that is, minivans. Some of them had signs with their destination, others didn’t. I didn’t see a van headed for Mogoditshane.

So I walked past row after row of minivans asking “Mogoditshane??” Eventually I found the section of the lot where those vans departed. I asked how much and a kid with a cloth bag said some number, I forget how much it was, but it was cheap. I was the third passenger. I settled down in my own row and was ready to depart.

We didn’t take off for a while. More people climbed in. When all the seats were taken, I was sure we’d be taking off. We didn’t, four riders per row was not full, even though that’s how many seats there were. Now one additional passenger had to squeeze into each row before we took off.

We didn’t take off for a while. More people climbed in. When all the seats were taken, I was sure we’d be taking off. We didn’t, four riders per row was not full, even though that’s how many seats there were. Now one additional passenger had to squeeze into each row before we took off.

Mind you, I had my suitcase with five weeks worth of clothes with me. It was a very tight fit. The ride back was usually not as tight, and eventually I was able to rent a dorm room at the university for a whole lot less, but I’d learned how to use public transport.

Later on that trip, I went to Mozambique. Unfortunately, I didn’t get to use a chapa there. A driver from the university made daily rounds picking up and dropping off visitors. My only public transit experience there was climbing onto the back of a large flatbed truck and holding on for dear life. The money collector, or cobrador, held a piece of rebar and anytime someone wanted to get off, he banged the truck’s cab with it.

Minivan taxis are the preferred means of transport all over the African continent.  They are called twegerane in Rwanda, dala dala in Tanzania, danfo or kia kia in Nigeria, fula fula in the DRC, matatu in Kenya and Uganda and tro tro in Ghana.

They are called twegerane in Rwanda, dala dala in Tanzania, danfo or kia kia in Nigeria, fula fula in the DRC, matatu in Kenya and Uganda and tro tro in Ghana.

The type of minibus may vary, for example, I found that in Pretoria, South Africa, Volkswagen vans were the dominant model (at least in 1999), which surprised me since Japanese makes dominated the streets in Cape Town. The colloquial names either refer to speed, as in “quick quick” or to the fact that there are filled past capacity, as in “stuffed.”

The degree of regulation of these taxi services varies from country to country. In Kenya they are tightly regulated. In South Africa, where minivans were prohibited under apartheid, the industry was deregulated after 1987. The result were loads of not roadworthy vans that were often overloaded. Taking these was risky. Add to that unregulated competition and you had the so called taxi wars. The statistics were gruesome. A report by Jackie Dugard claimed that in 1999 alone, some 258 people were killed and 287 wounded as a result of the violence between rival taxi gangs.

Several countries, including South Africa, have taken steps to impose more regulations on the industry. Still, those vans continues to be the way to get around. I can still hear the touts shouting “Wynberg, Wynberg,” luring passengers for the ride from Cape Town proper to the suburbs of Rondebosch and beyond. It was tight, but cheap.

Photo credits

Taxis in Manzini, Swaziland – Michael Niemann

Dala Dala in Tanzania – Muhammad Mahdi Karim, Creative Commons

Old Taxi Parki in Kampala, Uganda – Albert Backer, Creative Commons

Thanks, Elena. It’s great to be a guest on your blog.

Lovely to have you here!